Washburn-Crosby Elevator No. 1

1908, 1910

PDF of Washburn-Crosby Elevator No. 1 History

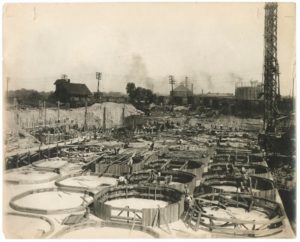

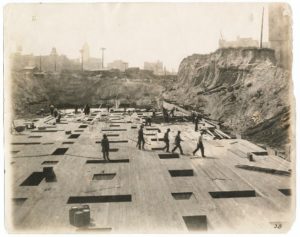

Constructed beginning in 1906 and completed in 1908, Elevator No. 1 was part of the larger Washburn-Crosby Milling Complex, situated in the heart of the West Side milling district. The milling district gave rise to Minneapolis’ title as the Flour Milling Capital of the World in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth centuries.

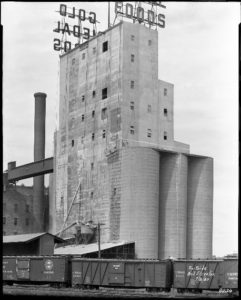

Washburn-Crosby Elevator No. 1 was constructed by the Haglin-Stahr Company of Minneapolis. The elevator was one of the first large-scale concrete grain storage facilities built in the United States using exposed circular bin construction. Elevator No. 1 consists of fifteen, 128-foot-tall cylindrical grain bins with a five-story headhouse structure on top. The elevator is an early example of slipform construction which allows the continuous pour of concrete throughout construction up to its 100-foot height.

The elevator is known for the Gold Medal Flour sign attached to the roof of the headhouse. The twin signs sit atop Elevator Number One. The signs are made of porcelain mounted on wood and are 42 feet wide and 45 feet tall. The signs were originally lit with 670, 15-watt incandescent bulbs. Each letter is 8 feet high. Bulbs were changed almost daily, even in the cold of winter.

Most mills in the world were small operations that served a city or town. The level of production of the milling industry in Minneapolis was on a scale not seen elsewhere. The flour milling industry took advantage of the economic boom in Minneapolis during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Minneapolis was the undisputed “Milling Capital of the World.”

In 1910, after the Gold Medal Flour signs were installed, The Minneapolis Tribune described the signs:

Like a signal fire flashing from a mounting top its story to a distant army, or the ray sent out upon a trackless sea from the lighthouse on the shore, speaking to the ships as they pass and repass, there stands today in Minneapolis a sign which nightly tells to the thousands and thousands of people coming and going, not only our own citizens but those who daily visit the great metropolis of the Northwest from all over the world, of one of the chief brands of the product which has made Minneapolis famous in all parts of the civilized globe.

Flour milling in Minneapolis peaked during World War I when the emphasis shifted from providing flour for home baking to commercial baking. World War I resulted in a food crisis overseas where allied troops were stationed. The mills in Minneapolis were among the first to respond to U.S. President Herbert Hoover’s Commission for Relief. After World War I, the Minneapolis milling industry began to decline.

Flour milling in Minneapolis peaked during World War I when the emphasis shifted from providing flour for home baking to commercial baking. World War I resulted in a food crisis overseas where allied troops were stationed. The mills in Minneapolis were among the first to respond to U.S. President Herbert Hoover’s Commission for Relief. After World War I, the Minneapolis milling industry began to decline.

Washburn-Crosby Company operated the mill along with more than 20 other mills in the area. Washburn called its brand Gold Medal Flour to differentiate it from its competitors.

In the early 1920s, the “Flour” portion of the sign was changed to “Foods” to reflect the diversity of products including cereals such as Wheaties.

In 1928, the Washburn-Crosby Company merged with 28 other mills in the area. This collection of mills was renamed General Mills.

The Washburn A Mill continued to operate for several more decades, even as the local milling industry declined. As the industry moved out of Minneapolis, the old mills fell into disuse. The Washburn A Mill closed in 1965. The Washburn Crosby Company operated the grain elevator until the mid-1980s.

In 2012, the Minnesota Historical Society commissioned a partial exterior preservation of the Washburn-Crosby Elevator No. 1, including replacing the roof of the bins and preserving the bin walls. Exterior concrete on the grain bins had cracked.

Openings in the windows, doors and concrete roof structures had allowed birds, rain, snow, and wind to enter the building further deteriorating the structure.

Preservationists restored the structure. The headhouse concrete roof was repaired and stabilized; the bin roof concrete was replaced with new pre-cast concrete; repairs were made to the exterior vertical sides of the bins, and the headhouse windows and door openings were sealed.

The Gold Medal sign was also repaired and restored.

The elevator is currently empty, but it is part of the Minnesota Historical Society and a National Historic Landmark.