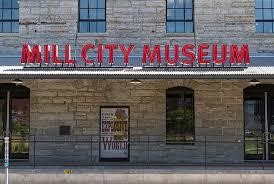

Washburn A Mill – Mill City Museum

1880, 2003

PDF of Washburn A Mill – Mill City Museum History

When Minneapolis was the “Milling Capital of the World,” the Mill City Museum was the Washburn A Mill.

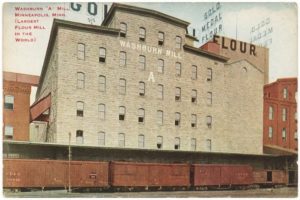

The Washburn A Mill, now housing the Museum, was the largest and most technologically advanced mill on the Mississippi River, producing enough flour to make 12 million loaves of bread a day. The company that operated the mill, Washburn-Crosby Company (now General Mills), played a significant role in the history of Minnesota.

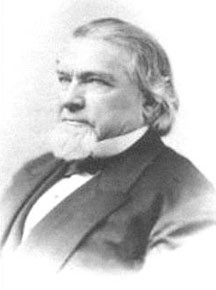

Shortly after Minneapolis was incorporated in 1867, Cadwallader C. Washburn, a businessman from Lacrosse, Wisconsin, built the state-of-the-art Washburn A Mill. The Mill was built on the Mississippi to take advantage of the power generated by the river and St. Anthony Falls. The Washburn A Mill, as well as other mills, helped make the area prosperous and ushered in a population boom. In 1870, the population of Minneapolis was 13,000, and within twenty years it grew to 165,000.

The Mill was ideally located with railroads bringing grain from the Dakotas and Minnesota, and trains traveling along rail lines delivering the milled flour to national markets. Arriving immigrants provided the labor force necessary to operate the mills.

The original A Mill began processing flour in 1874.

That same year, the first of several flour explosions at the mill leveled the mill as well as a large portion of the Mississippi riverfront.

In 1877, Washburn joined forces with John Crosby, renaming the company Washburn-Crosby.

A second explosion occurred at the mill in 1878. Due to poor ventilation, flammable flour dust particles accumulated in the Washburn A Mill. At six o’clock on May 2, 1878, the day-crew left the Mill; and fourteen men on the night crew arrived. An hour later, a spark ignited the flour dust, and the seven-story Washburn A Mill exploded, hurling debris hundreds of feet into the air. The explosion was heard ten miles away in St. Paul.

All fourteen mill workers were killed. Several adjacent flour mills also exploded killing four more workers.

In Lakewood Cemetery, there is a monument dedicated to the memory of the eighteen men who were killed. The monument lists the names of the men and includes an engraving with a sheaf of wheat, a millstone, and a broken gear.

In Lakewood Cemetery, there is a monument dedicated to the memory of the eighteen men who were killed. The monument lists the names of the men and includes an engraving with a sheaf of wheat, a millstone, and a broken gear.

After the destruction, Washburn, along with Austrian engineer William de la Barre, rebuilt the mill. De la Barre, using a sketch of a mill in Budapest, installed a new ventilation system to prevent flour dust collection. The new mill was completed in 1880 and touted for its state-of-the-art machinery that made the mill safer and produced some of the highest quality flour in the world. Each floor of the mill was used for a different purpose.

The Mill was the largest and most technologically advanced at that time using steel rollers instead of the traditional millstones.

Most mills in the world were small operations that served a city or town. The level of production of the milling industry in Minneapolis was on a scale not seen elsewhere. The flour milling industry took advantage of the economic boom in Minneapolis during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Minneapolis was the undisputed “Milling Capital of the World.”

Flour milling in Minneapolis peaked during World War I when the emphasis shifted from providing flour for home baking to commercial baking. World War I resulted in a food crisis overseas where allied troops were stationed. The mills in Minneapolis were among the first to respond to the U.S. President Herbert Hoover’s Commission for Relief. After World War I, the Minneapolis milling industry began to decline.

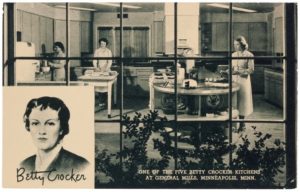

Washburn-Crosby Company operated the mill along with more than 20 other mills in the area. Washburn called its brand Gold Medal Flour to differentiate it from its competitors. In 1921, the Washburn-Crosby Company created the character Betty Crocker to help sell its flour.

After an October 1921 baking contest in the Saturday Evening Post, the company received a flood of phone calls asking about the contest. The advertising directors felt that the advice should best come from a woman. The name “Betty” was chosen due to its cheerful sound, and “Crocker” was an homage to former company director William G. Crocker.

In 1928, the Washburn-Crosby Company merged with 28 other mills in the area. This collection of mills was renamed General Mills. That same year, fire gutted the building again, and, again, it was rebuilt.

The A Mill continued to operate for several more decades, even as the local milling industry declined. As the industry moved out of Minneapolis, the old mills fell into disuse. The Washburn A Mill closed in 1965.

Although vacant, in 1971, the Mill was named to the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1983, it was named a National Historic Landmark.

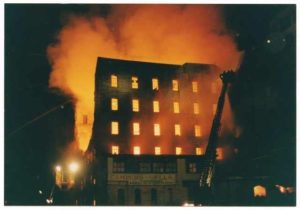

In February 1991, fire struck once again. Emergency responders were not notified until the flames had engulfed the building. By then, all that was left of the old mill were the concrete of the interior and the crumbling limestone walls.

Rather than demolish the remains, the city cleared the rubble and reinforced the mill’s damaged walls.

Shortly thereafter, the Minnesota Historical Society announced its plan to develop a museum on the site.

In 2003, the Mill City Museum, incorporating the ruins of the A Mill, opened to the public on the banks of the Mississippi River.

In 2003, the Mill City Museum, incorporating the ruins of the A Mill, opened to the public on the banks of the Mississippi River.

The Museum interprets Minneapolis’s milling history and the role of waterpower in the growth of the city. The Museum also offers visitors walking tours, hands-on exhibits, media shows including the Flour Tower, and sounds of the Mill operation itself.