Standard Mill / Whitney

1879, 1903, 1987, 2007

PDF of Standard Mill / Whitney History

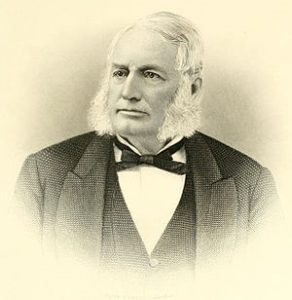

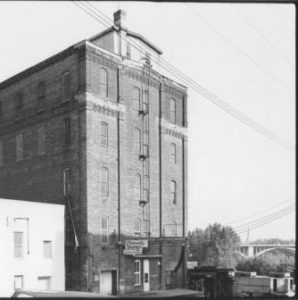

The Standard Mill was built in 1879 by Dorilus Morrison. Morrison had visited Minnesota from Maine in 1854 for business reasons and was sufficiently impressed by the area that he sold his Maine businesses and moved to Minnesota within a year. Morrison served in the Minnesota State Senate and was the first mayor of Minneapolis. He was also the first president of Northwestern National Bank of Minneapolis.

The Mill is significant for its association with milling engineers Dixon Gray and Otis Arkwright Pray. Gray designed and Pray built the structure.

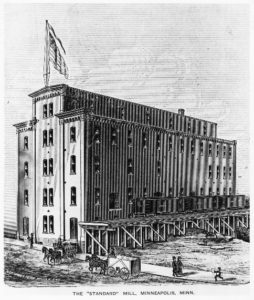

The Standard Mill was hailed as a model establishment. It received its name to call attention to its design. The four-story brick and stone building was built on Portland Avenue as a medium-sized flour mill. The mill was powered by a turbine water wheel in the basement. The first floor housed millstones and rollers for grinding grain, the second floor contained the packing department, and top floors were occupied by purifying and grading machinery.

The rear portion of the building was separated by fire brick and was used as a grain elevator with a 35,000-bushel capacity. An elevated railroad siding on the north side carried freight cars to the second floor for loading.

The mill began operations in 1879 starting with a daily capacity of 500 barrels. By 1880, daily capacity was 1,200 barrels, and by 1890, capacity was 2,000 barrels.

In 1880, Minneapolis became the largest flour producer in the country. The increase in flour milling created significant competition by the mid-1880s.

With so many flour mills in the area, overproduction would occur. When that happened, Morrison would suspend operation. Unless he could turn a profit, Morrison would rather cease production than keep his employees working.

At that same time, Minneapolis’ mills began consolidating, and in 1889, Dorilus Morrison joined with another milling company to form Minneapolis Flour Manufacturing Company with an aggregate daily capacity of 3,400 barrels of flour. By 1900, three corporations managed 97 percent of the total flour production.

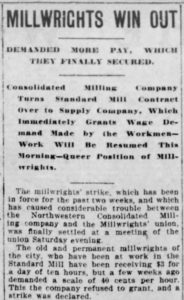

In April of 1903, the millwrights struck over a pay dispute. They had been working a ten-hour day and earning thirty cents an hour. They were seeking forty cents an hour. The workers’ strike was successful.

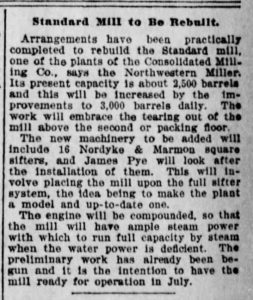

That same year, the building underwent a major remodeling to increase production from 2,500 to 3,000 barrels a day. Actual capacity increased to 3,500 barrels. Following the remodeling, the Standard was one of Northwestern Consolidated’ s largest mills.

During the 1930’s, there were serious declines in the West Side Milling District. Significant changes in wheat quality, freights costs, and tariffs impacted production. Minneapolis lost its place as number one in the country in flour milling.

The Standard survived the closure of many of the mills in the 1930s.

In 1933, the mill switched from waterpower to electricity.

In the 1940s, flour milling ceased at Standard Mill, and the building was converted to light manufacturing and warehousing.

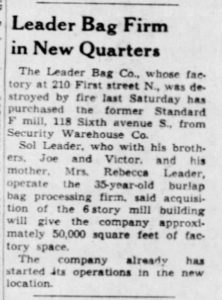

In 1948, following a fire in its own factory, Leader Bag Company acquired ownership of the Standard Mill building from Security Warehouse Company. The building’s 50,000 square feet of space was to be used to manufacture burlap bags. According to the Star Tribune on February 28, 1959, Leader imported ten million yards of burlap a year to make its bags.

Advertisements in the Star Tribune for employees and product sales continued into 1962.

In 1971, the Minnesota Historic Preservation Office recognized the mill’s historic significance by naming it among the contributing properties in the St Anthony Falls Historic District. It was one of only four mill buildings still standing from Minneapolis’ days as the flouring capital of the United States.

In 1987, the Standard Mill was redeveloped into the 97-room Whitney Hotel. A new two-story entrance was built on the southwest corner of Portland Avenue and Second Street South.

In 2007, the building was converted into 27 condominium units preserving features of the original building including exposed brick and stonework, vaulted ceilings, and original beams. The Historic Preservation Committee approved adding balconies and raising the level of the riverside plaza to provide for underground parking.