Ogden Apartment Building/Continental Hotel

1910, 1948, 1992

Ogden Apartment Building/Continental Hotel Building History

The Ogden Hotel, at 68 South 12th Street, was built in 1910 and designed to be a residence for middle-class workers. It was billed as an apartment hotel. Apartment hotels were popular in Minneapolis for a brief period in the early Twentieth Century. Apartment hotels lacked kitchens, with residents obtaining meals from a common restaurant within the building. Minneapolis had grown between 1880 and 1890, from a population of 46,887 to 164,738. By 1910, there were 208 apartment buildings in Minneapolis, with most of the buildings constructed close to the business district so that residents could be close to their workplaces as well as the city’s amenities.

Many of the residents stayed at the Ogden as a second home. On weekends, businessmen commuted to their homes on Lake Minnetonka or other western suburbs but lived in residential hotels during the week. The early residents of the Ogden included ten schoolteachers, two lawyers, a bookkeeper, a stenographer, an owner of a lumber company, the president of Twin City Loan and Realty, and two secretaries. For many renters, their time at the Ogden was temporary while they were building homes or relocating businesses. Less than half the original tenants were still residents a year later.

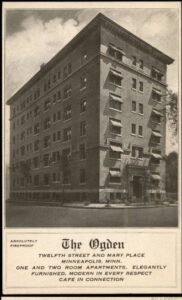

The building was named for its developer, J.K. Ogden. For many years, the only structure in the area was the Hugh Harrison home on Nicollet Avenue. The Ogden was designed to be the most up-to-date apartment building in Minneapolis. A.L. Dorr was the architect, and Ingeman Company of St. Paul was the general contractor. The estimated cost was $100,000.

The building was designed in the Second Renaissance Revival style and built of reinforced concrete, hollow tile, pressed brick, and terra cotta. The building was designed to be fireproof with reinforced beams and columns.

The 45 x 108-foot building faces 12th Street. The symmetrical facade is three bays wide. There is a raised limestone basement covered with terra cotta tile. The entrance has sidelights and a transom framed by terra cotta entablature with modillions and a pair of lion’s heads. The door is copper-finished.

The first two floors are faced with reddish-brown terra cotta brick; the third, fourth, and fifth floors are covered with reddish-brown brick; and the top floor is covered with yellow-gold brick. There is a decorative band of terra cotta dividing the top two floors.

The LaSalle side of the building has nine bays, and the exterior is finished in the same brick as the 12th Street side of the building. The opposite side and the rear of the building have buff-colored brick walls.

The entrance to the building was originally on the second floor, up a flight of stairs. When built, the Ogden Hotel was slated to have a twin building next door, but that phase did not happen.

The interior of the Ogden was designed for sixty-six one-bedroom and five two-bedroom apartments. All the rooms originally had Murphy beds.

In the 1920s, zoning law changes allowing for larger apartment buildings began to change the marketplace. Residential hotels lost their appeal to the typical businessman. The addition of highways in the 1950s also changed the market.

In 1948, the Ogden’s name was changed to the Continental Hotel, and the basement and first floor were remodeled. Ultimately the building’s clientele were lower-wage service employees, and some apartment hotels gained a reputation for housing people with chemical dependencies. Many owners of apartment hotels did not maintain their buildings, and they often fell into disrepair.

Over the years, Continental ran advertisements in the local paper reflecting the availability of rooms.

In July of 1953, The Continental Hotel made the news when it refused to accommodate a black woman who was temporarily in Minneapolis to study at the University of Minnesota. Public apologies were issued, and the Continental changed its policy.

In July of 1968, the Continental made the news again when its payroll office was robbed. That same month, Continental employees went on strike picketing the hotel for better hours—to reduce their 45-hour, six-day-a-week schedule to a 40-hour, five-days-a-week schedule.

The Continental Hotel made the news again with an article in the Star Tribune on March 5, 1983. William Morse owned and lived in the Continental Hotel at that time, and Henry Bernier was its handyman. When Morse was incapacitated, Bernier took care of him and managed the Continental. Morse willed his estate to Bernier.

Morse had been married in 1930, to a woman with two sons. Morse’s wife died in 1939, and Morse had severed his relationship with the two sons. The will was challenged (Morse had died five hours after signing it), and following a trial, Bernier’s share of the estate was reduced to $400,000.

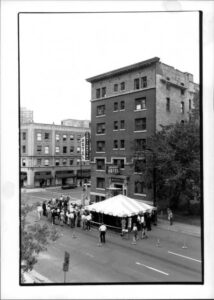

In 1992, the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the last remaining single-room residential structure in Minneapolis.

Also in 1992, the building was purchased by Aeon, then known as Central Community Housing Trust. Aeon is a non-profit developer which owns and manages affordable apartments and townhomes across the Twin Cities.

A groundbreaking ceremony took place in 1992 (captured in the photo at left). At the time of the purchase, there were few remaining residents.

In 1993, the property received the Neighborhood Environment Award from the Minneapolis Committee on Urban Environment.

Aeon rehabilitated the building into 66 affordable apartment homes. All the units now have kitchen facilities. Two larger shared kitchens were also added. Aeon was able to save many of the Murphy beds, some of which are still used. Aeon moved the entrance to the garden level.

Aeon’s renovation won the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission Award in 1995.