J.I. Case Building

1907, 1990s

PDF of J.I. Case Building History

The J. I. Case Building is located on the southeast corner of the Washington Avenue South and Park Avenue intersection in Minneapolis’s Downtown East neighborhood. From 1907, the year construction was completed, to 1936, the building’s street address was 701 Washington Avenue South. The entrance was shifted to the west facade in 1936, and the current address is 233 Park Avenue.

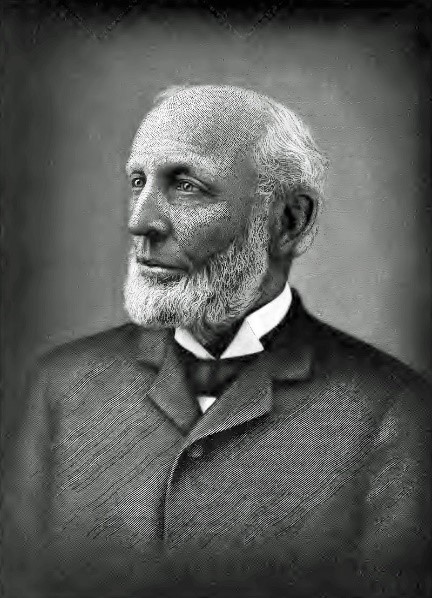

Jerome Case, an inventor and entrepreneur, played a leading role in agriculture’s transformation in the last half of the nineteenth century, and the company he founded continued through the twentieth century. Case experimented with ideas to improve the design of farm equipment, producing his first threshing machine in 1844.

Business grew, leading Case to form J. I. Case and Company in 1863, renamed the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company in 1880. Case diversified into related products and had become the largest steam-engine manufacturer in the world by 1886. The company developed a reputation for high-quality products and good customer service.

In 1882, the J. I. Case Plow Company began selling its line at 308–310 Third Avenue North in Minneapolis. The J. I. Case Implement Company registered with the state in 1883. By 1900, the J. I. Case Implement Company had expanded to 308–314  Third Avenue North. An advertisement inside the back cover of the 1900 City Directory described Case Implement as “jobbers of J. I. Case plows, Mitchell farm and spring wagons, [and] Hoosier seeders and drills,” and it had “a full line of carriages, buggies, farm implements, twin, bicycles and harness always on hand.”

Third Avenue North. An advertisement inside the back cover of the 1900 City Directory described Case Implement as “jobbers of J. I. Case plows, Mitchell farm and spring wagons, [and] Hoosier seeders and drills,” and it had “a full line of carriages, buggies, farm implements, twin, bicycles and harness always on hand.”

The Company’s sales doubled to $3.3 million during the 1890s. By 1890, the company’s products were distributed worldwide and carried by over one thousand dealers across the United States.

An article in the Minneapolis Tribune in January 1896 reported that “the Case Threshing Machine Company has had a big gain in this fall’s business, aggregating not far from 100 per cent.” Minneapolis was the top city for sales of farm machinery. Soon, Case’s operations, like other businesses in the original warehouse district, needed more space.

By the turn of the century the position of Twin City wholesalers had become firmly established. Agricultural equipment was a leading sector, and in January 1896, the Minneapolis Tribune proclaimed the city “the greatest distributing point in the world” for farm machinery. The momentum continued into the twentieth century.

The proliferation of implement companies in the last half of the nineteenth century was the result of momentous advances in farming technology, including the introduction of the threshing machine. Threshing machines streamlined several steps in harvesting grains and other crops. Threshing machines were initially powered by animals but were later linked to steam engines.

The proliferation of implement companies in the last half of the nineteenth century was the result of momentous advances in farming technology, including the introduction of the threshing machine. Threshing machines streamlined several steps in harvesting grains and other crops. Threshing machines were initially powered by animals but were later linked to steam engines.

By the early twentieth century, vacant land in the North Minneapolis warehouse district was scarce and companies seeking larger sites began looking elsewhere in the city. This need had been anticipated by William Henry Eustis, a lawyer and real estate investor who served as the city’s mayor from 1893 to 1895. William Eustis promoted a new district on the southern edge of downtown and had attracted some implement companies by the early twentieth century.

The area’s reputation was stained, however, by “Fish Alley,” an area tucked behind the buildings on the south side of Washington Avenue between Park and Chicago Avenues. A fish market had once occupied one of the buildings, giving the alley its name. A Star Tribune article on March 25, 1900, headlined, “The Passing of Fish Alley,” described the area as the “slum of all slums,” noting that the area “is more heard of in the police court annals than in the society columns of a newspaper.”

The article continued, “The police have their hands full in this locality. Only the hardiest of officers are able to cope with the people of the locality.” The article went on to state, “Woe be to the stranger within the gates of Minneapolis who chances to wander near this block.”

Leading from the alley were five or six stairways extending to apartments above. Every building in the vicinity sheltered more people than there was room for, and, as a result, there were many entrances and exits. Law breakers could easily make their get-away when pursued by the police. Petty thieves, pickpockets, hold-up artists and con men of all sorts frequented the area.

The area’s sordid reputation was augmented by a dance hall and four saloons fronting Washington Avenue on the same block. Newspaper articles in that last decade of the nineteenth century through the first decade of the twentieth continued to report numerous crimes in the area.

Until Fish Alley was eradicated, William Eustis knew it would hamper the area’s redevelopment. Several years after leaving city hall, he persuaded A. G. Wright, president of the Advanced Thresher Company, to build in the neighborhood. Eustis and Wright’s faith in the neighborhood paid off. The area soon became populated by warehouses for agricultural businesses.

Several years after leaving city hall, he persuaded A. G. Wright, president of the Advanced Thresher Company, to build in the neighborhood. Eustis and Wright’s faith in the neighborhood paid off. The area soon became populated by warehouses for agricultural businesses.

In 1906, when Case acquired the property, the Fish Building, for which the alley was named, was razed. The J. I. Case Building was built in its place in 1907 and was operated as a branch house of the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company.

During the five decades that Case occupied the Minneapolis building, American agriculture went through a radical transition, with mechanical power replacing animal power and small farms consolidating into larger operations.

Case was aware of the building’s symbolic importance. While Case’s Minneapolis branch was smaller than other implement company warehouses in the southside district, it claimed a far more prominent location on Washington Avenue, a major downtown artery, and its classically influenced design was modern compared to the nineteenth-century motifs displayed by the buildings of competitors.

A three-dimensional depiction of Case’s trademark, an eagle, crowned the building’s rooftop at the corner at Washington and Park. It was fashioned after an eagle that had been captured as a young bird, grew up as the pet of a Wisconsin family, and served as the mascot of a Civil War regiment, where it was named Abe after President Lincoln.

According to the Guide to the Industrial Archeology of the Twin Cities, “By 1908 Minneapolis could boast that it was the largest distributing point in the world for agricultural implements. By 1915 the manufacture and distribution of farm equipment had succeeded the flour and grain trade as the biggest business in Minneapolis in dollar volume.”

Case’s production of steam engines peaked in 1911. It logged record-breaking sales the following year, followed by a precipitous drop. Case produced its last steam engine in 1927. The company had enjoyed a prolific half-century, manufacturing around one third of all the steam-powered agricultural equipment in the country. Farmers bought 35,737 Case steam engines, more than double the volume of the nearest competitor.

World War I accelerated the mechanization of agriculture in America. Many farmers entered the military, creating manpower shortages and the demand for labor-saving machines in rural America. Case designed tractors to address that need, joining more than 150 manufacturers in the highly competitive industry in the 1920s.

By the 1920s, threshers had been upstaged by combines, which could both harvest and thresh the crops. Case introduced its first combine in 1920. The new machines were a substantial investment. Despite the economic depression in the 1930s, combines were commonplace by the end of that decade, and threshing machines had shrunk to a small percentage of Case’s business.

By 1930, only nine implement manufacturers remained, together producing 196,000 tractors that year. As farm tractors continued to evolve in the first half of the twentieth century, Case ranked third among American manufacturers.

As the company moved further from its roots, “threshing machine” was removed from the name of the business, which was henceforth called the J. I. Case Company. In the 1930s, the industry was challenged by drought and the Great Depression.

During World War II, Case’s manufacturing facilities were dedicated to the war effort. When the war ended, implement producers and dealers worked to meet demand from farmers for new equipment. Case made its last thresher in 1953.

Subsequently, the number of farms dropped sharply, with some 850,000 farms lost between 1954 and 1959. This loss was reflected in the sales of agricultural implements, which plummeted by 25 percent in 1960. Case’s financial situation reflected the tumult.

The decades after World War II were a low point for downtown Minneapolis. Increasing traffic snarled the city’s streets, delaying delivery trucks.

The condition of the older building stock, already decaying by the early twentieth century, was noticeably worse after years of deferred maintenance during the depression and war.

Washington Avenue became, once again, the main street of Skid Row, an uncomfortable setting for Case’s workers and agricultural clientele.

As in other communities, Minneapolis’ problems intensified as businesses and families were drawn to the suburbs. The city suffered a particular blow in 1955 when one of its largest corporations, General Mills, announced it would relocate its downtown headquarters.

Case joined the exodus in 1959 when it moved to Eagan.

After Case moved out of Minneapolis, the Case building became a warehouse for Minneapolis House Furnishings.

In 1959, Minneapolis House Furnishings hired Liebenberg and Kaplan, architects, to design an addition to the building. The addition enclosed an elevated loading dock on the south side.

Minneapolis Housing Furnishings had showrooms and outlets at numerous locations. The property remained a furniture warehouse, showroom, and outlet until the 1980s. The company’s various locations closed following bankruptcy.

In the early 1990s, the building was remodeled into offices and a restaurant, the Old Spaghetti Factory. The Old Spaghetti Factory is an Italian-style chain restaurant in the United States and Canada.

The chain was founded in Portland, Oregon, on January 10, 1969, by Guss and Sally Dussin. The chain continues to operate throughout the United States and Canada. The local restaurant, which opened in 1994, closed in 2019.

The chain was founded in Portland, Oregon, on January 10, 1969, by Guss and Sally Dussin. The chain continues to operate throughout the United States and Canada. The local restaurant, which opened in 1994, closed in 2019.

The building is currently the home of Sherman Associates. Sherman was founded in 1979 by George Sherman. The company has developed more than $4 billion in commercial and residential assets. Its current holdings include over 8,000 housing units, four hotels, and approximately one million square feet of commercial real estate.

Sherman plans to remodel the building for both offices and a new restaurant. In 2020, Sherman Associates applied to the National Register of Historic Places for designation of the J. I. Case Building. Much of the information regarding the early history of the J.I. Case building is taken from the application for registration.

Sherman plans to remodel the building for both offices and a new restaurant. In 2020, Sherman Associates applied to the National Register of Historic Places for designation of the J. I. Case Building. Much of the information regarding the early history of the J.I. Case building is taken from the application for registration.

The Case building continues to edge Washington Avenue. The neighboring Advance Thresher and Emerson-Newton Implement Company Buildings, built before the Case building, as well as the 1910 Great Northern Implement Company Building still stand, all four buildings evidencing the area’s long history.