Hall & Dann Barrel Company

1880, 1884, 1896, 1906, 1985, 2016

PDF of Hall & Dann Barrel Company History

Today we think of barrels as containers for beer or distilled liquors, but in the 1880s, barrels were used to store flour ground in Minneapolis mills. Producing barrels was an important ancillary business to Minneapolis’ flour milling industry, and the Hall & Dann Barrel Company was the largest barrel-making shop in the city.

A cooperage is a shop that fabricates and assembles all parts of a barrel, and barrel makers are coopers. In the 1880s, cooperages were known as either “tight” shops or “slack” shops, with “tight” shops producing barrels that would contain liquids and “slack” shops producing barrels for dry goods.

Several flour mills in the city maintained their own cooperage shops. Cooperages that functioned independently of the mills were either “cooperative” shops – owned and run by the employees, or “boss” shops. By 1868, about fifty coopers were employed in Minneapolis, with the majority working in cooperative shops. Fabricating and assembling a barrel was a time-intensive process. The most skilled cooper produced a few barrels each day.

The original Hall & Dann barrel factory was located at the foot of the 10th Avenue South bridge. The Hall & Dann barrel factory moved to its new building in 1880 when Albert R. Hall and Marcus C. Dann formed a partnership to further invest in the cooperage business and construct a new, state-of-the-art building.

The June 23, 1880 Daily Minnesota Tribune announced, “The new cooper shop on the corner of Third Avenue South and First Street will be 60 x 172 feet in size and four stones high. The Hall & Dann Barrel Company are the projectors and owners.” The building was constructed in several stages, with additions completed in 1884, 1896 and 1906. At peak production, the factory turned out 6,000 barrels each day and employed about 175 men.

The June 23, 1880 Daily Minnesota Tribune announced, “The new cooper shop on the corner of Third Avenue South and First Street will be 60 x 172 feet in size and four stones high. The Hall & Dann Barrel Company are the projectors and owners.” The building was constructed in several stages, with additions completed in 1884, 1896 and 1906. At peak production, the factory turned out 6,000 barrels each day and employed about 175 men.

Barrel making was a highly skilled trade, and the coopers were well paid and steadily employed. With well-paid and steady employment, it did not take long for there to be an overabundance of coopers, and with this oversupply, wages declined. The barrel-making industry experienced labor problems long before the Hall and Dann Barrel Company began operation. The coopers had their wages cut in 1874 and a strike ensued.

The Hall & Dann Barrel Company — one of few “boss” cooperages — experienced its share of labor problems as well. In July 1882, the workers went on strike, protesting a decline of two cents per barrel in their wages. The owners had been paying two cents per barrel higher than other cooper houses in the city, and when the price was lowered to be on par with other cooper houses, the workers struck. Management reinstated the original wage, and everyone returned to work.

In November 1883, the Daily Minnesota Tribune announced, “The coopers’ shops are running about the usual number of men now, though whether this will last depends on the flour mills. Unless there is a call for immediate use of barrels, they will not turn out many, as they are damaged by being stored. The recent troubles with the men at the Hall & Dann Barrel Company has been satisfactorily settled. They are now getting the old price per barrel at which they are able to earn, on average, $2.50 a day.”

In 1886, the issue of compensation arose again. Coopers throughout Minneapolis began a formal strike. Coopers from the east bank marched to the west riverbank, adding to their numbers with each stop. One hundred and thirty-five men joined the march at Hall & Dann, and by nightfall, every cooperage in the city was closed. The coopers had been working for 12 to 14 cents per barrel and requested an increase in pay to 16 cents per barrel. The October 13, 1886 Daily Minneapolis Tribune reported, “A lively open-air meeting was held at Schaefer’s beer garden…. The general opinion seemed to be that they could easily gain their point because none of the shops have a large stock [of barrels] on hand and the demand will soon increase the price.”

In the late 1880s, nearly all sales of flour were to the home baker. Flour was sold in 196-pound barrels. During the 1890s, cooperage shops experienced a decline in business, as bags began to be used for flour storage rather than barrels. The invention of the sewing machine enabled bags to be made in large quantities. Using bags rather than barrels to ship flour lowered shipping costs for the mills.

The bags also had resale value: in the mid-1920s, it became quite stylish to recycle flour sacks into clothing and decorative household items. The Great Depression turned the stylish trend into a necessity.

Flour sacks were also less likely to leak, although flour buyers often preferred barrels to bags, as the barrels provided greater protection against rodents. Continual labor issues in the cooperage business also contributed to its demise.

Although cotton bags eventually replaced barrels, the quantity of flour bagged mimicked the measurements that had been established by the cooperages. Bags were produced to hold ninety-eight pounds of flour, exactly one-half the capacity of a barrel. Eventually, flour packaging was standardized, to the 2-pound to 100-pound options that are available today.

Hall & Dann had anticipated the change from barrels to bags. The company leased space in its building to a bag manufacturer in 1885, and by 1890, the Hall and Dann Barrel Company was manufacturing flour sacks exclusively. With this change in the business model, the company name was eventually changed to the Northern Bag Company.

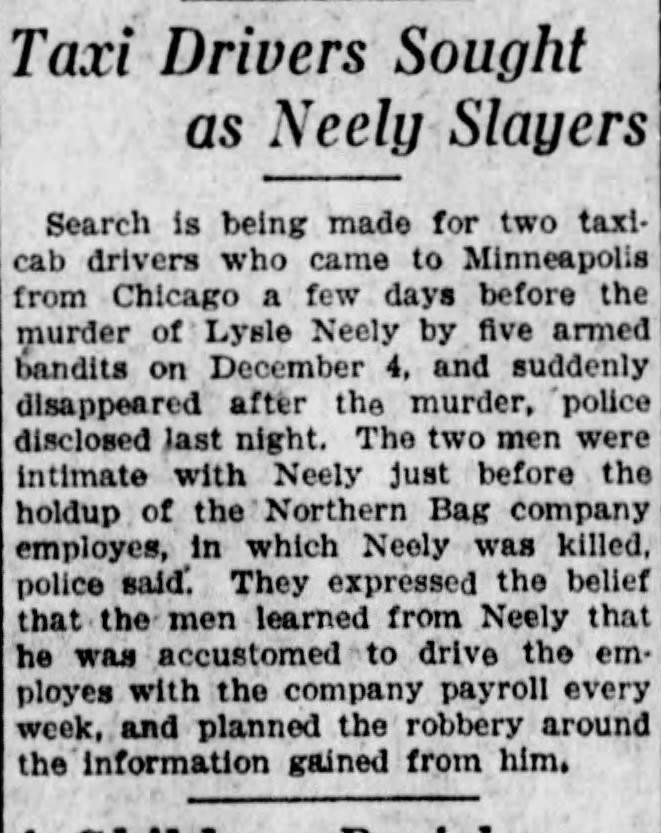

In early December 1920, the Northern Bag Company was held up by five armed bandits. It was believed that a Northern Bag employee, Lysle Neely, had told outsiders about his routine of driving company employees around town who were holding the company payroll. A robbery ensued, and Neely was killed.

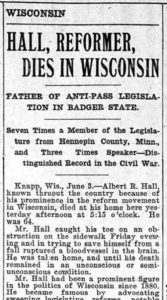

Albert Hall relocated to Knapp, Wisconsin to manage the company’s business interests there, which included a facility for making staves (the narrow slats of wood placed edge to edge to form the sides of the barrel). Hall died in 1905 as the result of a brain injury from a fall.

Since the days of Hall & Dann, the building has been used almost exclusively as a warehouse.

During the Depression years, the building was a storage facility for the Salvation Army.

Postwar, the building was purchased by Buick distributor, Win Stephens, and was used for car storage. New automobiles were brought into the back entrance to the building and moved to upper floors in a large freight elevator. The Minneapolis Star announced on March 30, 1946, that the facility could prepare approximately 9,000 cars a year for delivery to dealers.

Numerous want ads in the Minneapolis newspapers sought employees to work at the location.

In the early 1980s, redevelopment plans called for office space, retail on the first floor, and a restaurant in the basement.

By the time renovation was completed, the building was converted exclusively to office space.

The building was sold once again in 2016, substantially renovated to expose the original brick and timber materials, and renamed The Barrel House.

The Barrel House is the only 19th-century barrel factory still standing in Minneapolis today.