Columbia Mill / Fuji-Ya

1870, 1882, 1883, 1968, 2021

PDF of Columbia Mill / Fuji-Ya History

In 1972, the Mississippi riverfront was considered “the backside of the city of Minneapolis,” an industrial area containing abandoned mills, a sand and gravel storage area, and an active railyard. The ruins of the Bassett Sawmill, Columbia Flour Mill, and Occidental Feed Mill, all built in the 1870s and 1880s, were located at the site.

Bassett’s Second Sawmill, constructed in 1870 by Joel Bean Bassett, had a thick limestone foundation and a two-story wood-framed upper structure. The sawmill was destroyed by fire in 1897, but its engine house and boiler room survived and provided power to the neighboring mills.

The Columbia Flour Mill, built in 1882, was a six-story structure with four to six-feet-thick feet-thick limestone foundation walls, set onto bedrock, with brick upper stories. The Columbia Mill had a reputation for producing some of the best flour to come out of Minneapolis.

The Occidental Feed Mill, a two-story brick building with limestone foundation walls, was built in 1883. The Occidental burned down in 1919.

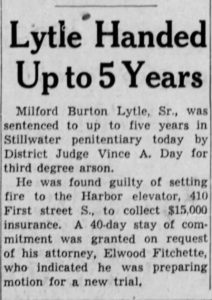

By the 1930s, the Columbia Mill had been converted to a grain elevator, known as the Harbor Elevator (also known as the Ceresota Flour Elevator).

When flames ripped through the elevator in 1941, the floors gave way, dropping 50,000 bushels of grain into the basement.

Portions of the limestone basements and sub-basement walls of the Columbia and Occidental mills survived the fires.

Milford Burton Lytle was found guilty of arson for setting the elevator on fire and sentenced to five years in prison.

In the 1950s, the lower surviving stories of the destroyed mills were backfilled with a variety of materials ranging from used tires to demolition waste.

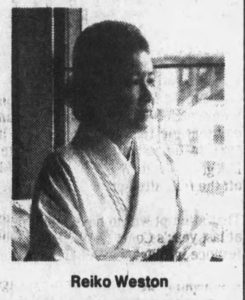

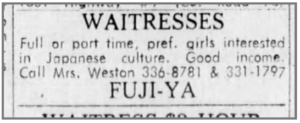

In the 1960s, Reiko Weston, a young Japanese immigrant, owned a popular restaurant in downtown Minneapolis that was outgrowing its space. Searching for a new location, Weston saw a for-sale sign on the burned-out shell of the Columbia Flour Mill. She purchased the property and hired Shinichi Okada and Newton Griffith to create the new restaurant.

Weston requested that the architects retain the thick foundation walls of the former buildings. The restaurant sat upon the historic ruins of the Bassett engine house and the Columbia boiler turbines that were still located in the basement and above the tunnels that were navigable under the nearby Crown Roller Mill.

Fuji-Ya opened in 1968, the first Japanese restaurant in Minnesota. A few years later, Weston opened a sushi bar in the space, also a first in the state. The structure, built of rough cedar and oak, included floor-to-ceiling windows facing St. Anthony Falls and the Third Avenue Bridge. Seating included booths, as well as traditional Japanese-style tatami mats. Servers wore Kimonos.

The restaurant’s proximity to St. Anthony Falls and the Third Avenue Bridge was considered good luck.

Weston appreciated the beauty of the riverfront location at a time when few ventured into the area.

Fuji-Ya, as well as Weston’s other restaurants in the Minneapolis area, was highly successful.

Reiko Weston was named Minnesota’s Small Businessperson of the Year in 1979 and was inducted into the Minnesota Business Hall of Fame in 1980.

Weston’s restaurant not only drew attention to the Mississippi riverfront at a time when there was no other commercial activity in the area, but it also played a key role in connecting the city to the river and stimulating the eventual revival of the flour milling district.

Fuji-Ya closed in May of 1990, and the property was purchased by the Minneapolis Park Board. While many plans were brought forth for the development of the former Fuji-Ya site, the site remained vacant for twenty-seven years.

Beginning in the fall of 2017, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board conducted selective deconstruction of the building, and an extensive archaeological examination of the former mill site was initiated. Deconstruction was carefully done to protect and preserve the historic mill ruins and incorporate artifacts into new construction. Just as Weston had requested that the architects retain the thick foundation walls in the building of her restaurant, ruins and remnants from the 1800s remain today. The site of the former mill, engine house, and Fuji-Ya restaurant has been transformed into the new Water Works Park Pavilion, which includes a visitor center and the riverfront restaurant, Owamni by the Sioux Chef.

The restaurant is located on the sacred Dakota space of OwamniYomni (“the place of falling, swirling waters”). Partners Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson offer both dine-in and take-out Indigenous foods, with a mission to promote Native American cultures, honor plants and natural resources, and encourage and foster an Indigenous food movement.

The restaurant is located on the sacred Dakota space of OwamniYomni (“the place of falling, swirling waters”). Partners Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson offer both dine-in and take-out Indigenous foods, with a mission to promote Native American cultures, honor plants and natural resources, and encourage and foster an Indigenous food movement.

The Water Works Park site serves as an acknowledgment of this spiritual place that has historically been the center of culture and commerce for native people and immigrants and is the birthplace of Minneapolis’ once vibrant milling history. St. Anthony Falls has been a gathering place for thousands of years. It was a place of encampment for Indigenous people who gathered here to share in the spiritual powers of the falls. Later, this place became the place of settlement for immigrants employed in flour milling and sawmills.

Owamni’s food celebrates the plants, animals, birds, and fish native to this region, and as such, will not include the wheat flour that was shipped from the mills in this neighborhood by the barrelful and literally put Minneapolis on the map.